Chapter 5: The guises of winter in overlapping layers of white

While there is nothing wrong with easily comprehensible and explicit colors, shapes and materials, the unparalleled elegance of wagashi (Japanese sweets), which combine abstract forms, textures, and enigmatic names to bring the qualities of each of the seasons into clear focus in our minds, presents something that is so much more exciting intellectually.

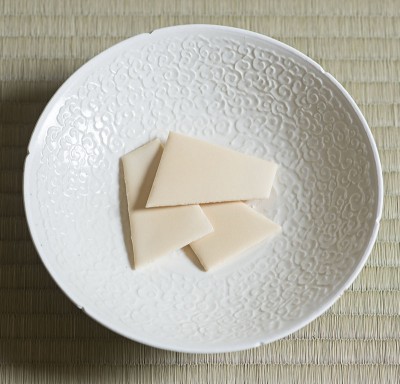

Vessel: Hakuji Inka Kinugyokutomon Wan by Yuzuru Harada.

Sweet: Usugori by Usugori-honpo Goromaruya.

Photo by Tetsuka Tsurusaki. Cooperation: Kashima Arts.

I find myself particularly strongly attracted to winter sweets that conjure images of snow and ice. Shimobashira (lit. “pillars of frost”) is a silvery white candy confection that looks like bundles of fine thread. Made by Kokonoehonpo Tamazawa in Sendai, this would have to be Eastern Japan’s superlative confection for someone of my tastes. Meanwhile, I would pick Usugori, a type of dry candy produced by Usugori-honpo Goromaruya in Toyama, as the greatest confection found in Western Japan. Usugori (lit. “thin ice”) are made by brushing wasanbon sugar that has a delicate tinge of unbleached color onto thin pieces of senbei (rice cracker) dough.

Usugori were first produced in the year Horeki 2 (1752), during the Edo period. This was an age when brilliant painters such as Jakuchu Ito, Okyo Maruyama, and Shohaku Soga vied for attention in Kyoto. Meanwhile, Tokugawa Yoshimune, the eighth shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, whose reign had been held in high regard, had died in Edo just the year before. It was the fifth-generation head of Usugori-honpo Goromaruya, Hachizaemon, who created the first Usugori, inspired by thin sheets of ice over rice fields and pools of water. From the reign of Maeda Narinaga (1782–1824), the eleventh daimyo of the Kaga domain, onwards, Usugori came to be presented to the shogunate as a gift from the domain each time the local daimyo had to take part in the obligatory system of alternate attendance in Edo.

With simple sweets, a good sense of balance is achieved if the plate on which they are presented is complex in its design and production technique. Teiyo, a kiln that developed in Hebei Province, China, from the time of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, through the Northern Song, and into the Jin dynasty, became famous for its white porcelain production. Particularly from the latter years of the Northern Song dynasty (11th–12th centuries) onwards, the kiln came to use a decorative technique known in Japanese as inka. This technique, in which a pattern is impressed onto the surface of the porcelain using a mold, was well suited to mass production. The potter Yuzuru Harada uses this classic technique to create patterns on white ceramic plates, thin forms that have a feeling of tension. These include not only traditional auspicious patterns from China but also patterns derived from east and west Asia and also from the Christian world.

Looking through this frozen ice, we begin to decode the pattern of this plate, with its complex weave of myths, legends, and prayers for happiness and prosperity from various lands. It may just allow for a moment of travel that goes beyond present time and space.